SniaFiocco, The Textile of Independence. From Lidel, June 1933, Biblioteca Nazionale, Rome.

Under Fascism, fashion and film were both identified by the totalitarian regime as powerful vehicles for shaping and projecting national identity and a politics of style. As such, they became recognizable cultural institutions of Italian modernity. No government in post-unified Italy (the period from 1860 onwards) had been able to create anything like the distinct image with which fascism made itself visible: the black shirt, which still today epitomizes the image of fascism and the Duce. Fascism understood very quickly how powerful a medium cinema was for the diffusion of visual messages. It was with massive State support, in fact, that Italian cinema rapidly developed in the 1930s. In the early 1930s, the first regime-sponsored fascist propaganda feature films were made such as Gioacchino Forzano’s Camicia Nera (Man of Courage, 1933), the story of the reclamation of the malaria ridden Pontine marshes by the regime, and Alessandro Blasetti’s Vecchia Guardia (1934), celebrating, twelve years on, the March on Rome and the “success” of the regime in saving Italy. However, overtly propagandistic feature films such as Camicia nera and Vecchia Guardia were in the numerical minority when compared to the other genres of film made under fascism. In fact, it is inaccurate to think of film under fascism as merely a vehicle for political propaganda. Things were much more complex than that. A study of film under fascism involves an in-depth investigation of the stylistic forms adopted in the filmmaking of the period. Not only did fascism see in cinema a powerful medium that would help it achieve its ends, it also saw fashion in the same way. In fact, the regime invested a great deal of energy in and exercised state control over the fashion industry. It was under fascism that fashion and film first travelled at the same speed.

In 1932 and then renamed in 1934, Mussolini founded the Ente Nazionale della moda (ENM, National fashion body). The aim of this government institution was to control the entire productive cycle of textile and fashion. But in line with the regime’s totalitarian project to create new Italian men, women and children, it also aimed at inculcating an Italian fascist lifestyle through dress codes. In fact, one of the credos of the ENM was to persuade female consumers and dressmakers to seek inspiration in Italy’s domestic roots and traditions.[i]

Dress in printed silk in blue, gray and purple, by Fercioni. Biblioteca Nazionale, Rome.

Following the crisis in the post WWI years of the Italian film industry it was in the 1930s, the period of the consolidation of the fascist regime, that Italian cinema saw an important moment of rebirth with the inauguration of the “Città del cinema” or Cinecittà and the school of cinematography, the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia, hereafter CSC. This was part of the massive reorganization of both the film industry and educational institutions that took place under the fascist regime. It was also at this time that the fashion industry was organized under several national boards and state controlled institutions and was greatly promoted through the media, film, newsreels of the LUCE Institute, periodicals, fashion shows with lively mannequins and also fashion exhibitions in several Italian cities (Milan, Turin, Rome and Venice).

Fascism saw the great potential of fashion and style as tiles in its construction of a “new” Italy and “new” Italians. Cinema, under fascism, received “enormous state subsidies, both for the documentary Cinegiornale LUCE newsreels and the commercial film industry.”[ii] Inaugurated in 1937, Cinecittà was the largest film studio in Europe; at the same time the Centro sperimentale di Cinematografia (CSC), the Italian film school, housed in Cinecittà, was also inaugurated.[iii] In “Come si impara a far del cinema” (How to learn cinema), an article published in the journal Cinema,Luigi Chiarini, director of the CSC, painstakingly recorded the work students did at the Center, stressing the amount of study that was required for those who wanted to work in the film industry. [iv]

Fashion in Motion: The L.U.C.E. Newsreels. LINK to samples of newsreels

The Unione Cinematografica Educativa (Educational film union, Luce) was created between 1924 and 1925 as one of the most important institutions for regime inspired education and propaganda. The Institute was initially founded as a private concern, but was taken over by the Italian State and received financial backing thanks to decree no. 1985, passed on November 5, 1925. From this operation, the financial capital of the institute was more than doubled. A later decree, n. 1000 of April 1926, made the dissemination of Luce productions compulsory in all movie theaters. But modernity had not yet reached every corner of Italy and there were many isolated and remote areas where no movie theater existed. With the intent of spreading the message all over Italy, in 1927 the Luce Institute equipped twenty-five Fiat trucks equipped with movie projectors and sent them to remote cinema-free Italian locations so that films could be watched. Not surprisingly, this was an initiative that turned out to be very successful with “thousands of spectators” who were extremely thankful to the fascist regime for its generosity (Pierluigi Erbaggio, in Bertellini, p. 226).[v]

With the Luce newsreels, we have the first cinematic documentation of fashion shows and fashion parades that had the specific aim of advertising Italian products.

Fashion in motion in the 1910s was conveyed through the divas in fiction films; now with the fascist regime we see professional models advertising fashion. It is relevant to note this shift in the Italian context and how the regime was “selling images of fashion as paths to modernity,” a phenomenon studied by sociologist Elizabeth Wissinger. She writes: “models led the way into a consumption-defined lifestyle by showing goods as a way to become part of the consuming community” (Wissinger: 69).[vi]The relationship between the promotion and propaganda of Italian fashion and the production of the Luce newsreels was not straightforward. Rather, the Luce newsreels featuring fashion, which began in 1928 and continued well after the fall of the regime, are complex and rich and certainly deserving of the attention of scholars from a variety of fields of expertise, not only from fashion history.

Hundreds of LUCE newsreels, now accessible through the Istituto Luce Digital Archive, covered fashion in the late 1920s and 1930s. . Even though Italian fashion had been nationalized and subject to policies that controlled production and marketing, the newsreels do not limit themselves to documenting and reporting on State initiatives. Two trends emerge from the newsreels: first, Italian fashion already appears linked to the traditions of several Italian cities (Rome, Turin, Milan, Florence, Venice) and historical locations with landmark architecture (Villa D’Este, Cernobbio, Como and others). The newsreels give no picture of a centralized Italian fashion, even in the throes of the regime’s nationalistic drive. Italian fashion appears to be the product of a plurality of fashion cities in the Italian peninsula (as it still is largely today); second, but not less important, in the newsreels we see massive attention given to foreign fashion from Paris, Berlin, Budapest, London, Sweden, even Shanghai and Mexico, and from the US, of course, clearly the main inspiration and the nation to which most space was dedicated. Analysis of the newsreels on fashion reveals two different components: one is the advertising and marketing strategies of the fashion film; the second is the use of the camera, the techniques of storytelling in a compressed time frame (usually about one minute or so), the formal aspects of the décor, landscape and background, the way models walk and their gestural performance.

Massaie rurali, Great Parade of Female Forces, Rome, May 28, 1939, Istituto Luce, Rome.

In her entry “La moda di ieri e di oggi” in the 1939 Enciclopedia pratica della casa (531, 32), Ada Salvatore writes of what is expected from a fashion model and what the most distinguishing features of her performance are in the many events organized under the regime. She says:

What we ask of these creatures is not only a perfect figure, a fine smile, gracefulness and especially an elegant and self confident way of moving. If you do not know how to walk you can’t be a fashion model. Some never learn. Others need training to a greater or lesser extent, in accordance with their natural talents. And then a certain understanding is necessary because you shouldn’t think that you can walk in the same way with different clothes. For morning or ‘sport’ clothes you need a swift and casual gait; for afternoon “outfits” comportment is less jaunty though still free and easy: the model opens the topcoat to show the lining, or she takes it off and puts it on her arm or lets it drag along the carpet with well-mannered negligence. Evening clothes call almost for a certain solemnity of attitude, proportional to their sumptuousness: the train should never appear as an encumbrance. And when you turn round, take care not to step on it or trip up![vii] (emphasis mine)

Salvatore stresses the importance of movement, gait and the gestural performance of the models, but also offers suggestions on the style to be adopted for modeling different kinds of clothing. She gives emphasis to the performance of a constructed naturalness, a certain sprezzatura, we may say, that shows off the clothing as if it belongs to the body that wears it and enhances its beauty. In a Luce newsreel of 1928, showcasing the “moda italiana a Milano,” models follow Salvatore’s tips, synchronizing their gait and movement according to the outfits they are wearing. Ample coverage is given to different fashion spaces such as an elaborate 1929 show at the Rinascente in Milan.

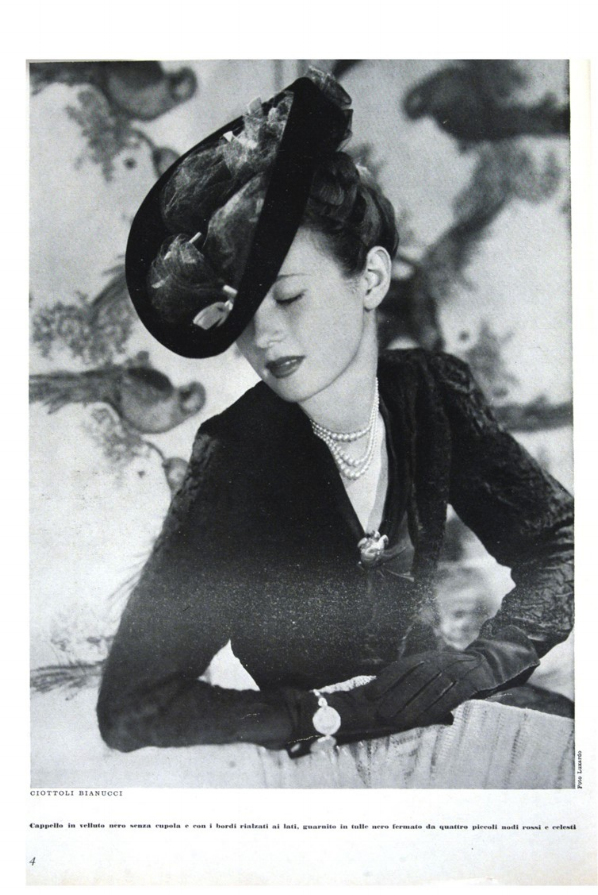

Black velvet hat, tulle trimming held in place by red and light blue knots. From Bellezza, September, 1942. Biblioteca nazionale, Rome.

It would be misleading to analyze the Luce newsreels, the hundreds of pictures published in fashion magazines and the photographs housed in several Italian archives and libraries solely in terms of political and ideological propaganda. Rather, they demand to be viewed in the wider context of film experimentation and theory, of their commercial aspect, and of the role that fashion and film have in the “Italian way to modernity” in conjunction with other film and documentary.

A Luce newsreel, aptly titled “Un originale sistema di presentazione della moda” (An original system of presenting fashion, B0373: 1933), focuses specifically on how best to stage fashion. This short does not just present fashion, it also focuses on the ways fashion can be showcased in the most enticing and appealing of modes. It is a sort of an instructional video. These modes are extrinsically cinematic and are very much at the core of fashion parades in feature films.

Proper fashion shows were to be incorporated into Italian cinema starting with Alessandro Blasetti’s 1937 film Contessa di Parma.

Every formal aspect in this 1933 Luce newsreel is curated; particular attention is dedicated to the role of stairs and mirrors. The stairs trace a circular trajectory and the model is filmed while descending them; she then walks towards the mirrors, strategically positioned to multiply her image and create an optical effect almost like an abstract canvas. At the same time, the presence on screen of two objects in the décor such as the staircase and with it the physical act of walking and the mirror, which hints at a pause and a pose, is particularly significant. The dynamic between the staircase and the mirrors produces cinematic space. The fashion film makes explicit the relationship between fantasy and reality and what can be constructed and faked. In fact, some of the frames freeze the multiplied image of the model in front of the mirror and viewers perceive the space and the spectacle in its mediated form: the camera and the mirror. The staircase and the mirror bring to the fore the dynamic between movement and the pose as we saw in the previous chapter in reference to Bragaglia’s photodynamism, “the intervals of duration.” In fact, this particular newsreel in its initial pedagogical intent brings to the fore how fashion in film through clothing and objects and the body of the model mimes and renders explicit the role of montage. In his book Montage, film scholar Sam Rohdie has examined the forms and complexity of montage in specific films. He writes, in fact:

The filmstrip is made of still frames, that when projected at a set speed of 24 frames a second, give the illusion of movement and continuity. Film has had to reconcile these contrary directions of stillness and movement, continuity and rupture, and has done so in one manner or the other, most often in the variations of the two. […] Montage simply is the joining together of different elements of film in a variety of ways, between shots, within them, between sequences, within these. (Rohdie, Montage, p. 1)

Especially crucial for fashion in film and for filming fashion is the “illusion of movement.” Indeed, the illusion of movement is even greater today than it was for Eadwaerd Muybridge, to whom the first chapter of Rohdie’s Montage is dedicated. The movement then becomes dematerialized in the intervals of duration, between the staircase and the mirror we see in the 1933 Luce newsreel. Rohdie’s book concludes with Marey’s experiments and explains the core differences between the two approaches to movement and stillness and the gaps in between them. In referring to Muybridge’s photographic experiments of 1887, when he reproduced bodies in movement in a sequence of stills, Rohdie observes that:

These reproductions, though sequential, were composed of intermittent, discontinuous immobile units, in effect, a linked series of snapshots. Nothing moved, no body, no animal, no stick, no ball, no hand nor eye, nothing went from here to there. The sensation of movement was realized by the construction of a logical and progressive line between one image and the next. Movement was not seen, but imagined in the gaps between instances of stillness. Muybridge’s locomotion studies though appearing to be successive moments of a continuous movement were at times faked. In these cases, he had his models pose in a succession of gestures imitating rather than enacting movement. A Muybridge nude descending a staircase or washing linen might, for example, hesitate at each step or each stage of the process. It was her pose in suspension that Muybridge photographed as if in movement. (Rohdie: 2-3)

“As if in movement” is what is at stake in staging fashion, in every way akin to the “perennial debates concerning film” that “involves the difference (and opposition) between the realistic (natural, real-seeming) and the real” (Rohdie: 104). In this way, the Luce newsreels, and especially those on fashion, need to be considered in the larger context and debate about film and image, and how fashion is relevant to this debate.

Milan: Modernity, Fashion and the City

Stramilano is a portrait of daily life in the city from dawn to night. This film expands the horizon of investigating fashion in relation to film and the city, and the city and fashion. D’Errico’s film, in fact, includes two long episodes, one dedicated to the production of textiles; the other to a fashion show in a prestigious Maison in Milan. But before discussing the fashion show in D’Errico’s film, let us turn to what comes before it. Milan appears as a modern and industrious city. The pace of the film is quite frenetic; images of factories and machines alternate with those from nature, and close-ups of animals and cows, the image of a food market and trams running toward the viewers. At the beginning, we see a medium shot of the garbage collectors who clean the city streets early in the morning when the city is enveloped in fog. This is certainly a shot that recalls one of Michelangelo Antonioni’s early documentaries, to which we will refer in the following chapter. At times the factories are framed in such a way that they resemble abstract paintings, which will be another characteristic of Antonioni’s filmmaking. After this, a long sequence follows the production of textiles, one of the regime’s commercial success stories. We move from inside the factory, where we see a cascade of fabric and cloth, different kinds that fill the screen, as in the case of a print fabric that morphs into the screen, to the warehouse where the fabric is packaged and ready to be sent. Here we see men and women working and moving among the hundreds of packages to be sent to shops and fashion houses. Immediately after the intense spectacle of textile production, which presents Milan as the center of modernization and work, we are introduced to a sophisticated locale. Here we find three elegant young women, the customers waiting to view the clothes worn by the models about to parade before them. A more mature woman, who seems to be in charge of the house, enters with the models. From the pictures published in several fashion magazines of the time she seems to be Marta Palmer, a famous and creative dressmaker who had been active since the 1920s and had been very keen to explore clothing as a form of art. Her casa di moda had already been featured in 1919 in the periodical La Fiaccola. Rassegna Femminile d’Italianità in an article by Elisa Albano where she describes Palmer’s atelier frequented by painters, musicians and writers as an expression of her creativity in a space where she exhibits dolls dressed in children’s clothing. She adds that:

Women who are young, beautiful, ugly and more mature, slender and […] shy and aggressive, intelligent and ordinary, bourgeois, aristocratic, artistic come and go to Palmer and ask her advice, directions and definitive decisions for how to dress with taste, in order to be certain to interpret their type in the style of dress, as it is the right aspiration for any woman, after the famous creation of Eve who started clothing and then fashion. […] her hands [Palmer’s], her brain, her fantasy are continuously running, producing rich fabrics, clothes that are masterpieces of grace, original draping, pleats never seen, new combinations of style and colors…[viii]

The article in question shows the artist and entrepreneur Maria Monaci Gallenga, who became well known for her textile design, wearing and graciously posing with a Marta Palmer dress whose print recalls Gallenga’s fabric. Ten years later, Palmer also stressed an international vision of fashion, arguing that “copying” was an integral part of fashion design and that perhaps it was an illusion to think of essential and original clothing that did not include various references to others’ designs (but she also maintained that dresses such as her own “Ball day” were not copied).[ix]

The fashion show in Stramilano is elegantly staged in an intimate setting. The models’ gait is flattering, almost flirtatious; every gesture calls attention to a particular detail of the dress. The gowns are in shiny satin, fur trims and opulent collars accompanied by accessories like beautiful big fans in feathers or lace. Some of the models seem to walk so lightly that they resemble ballerinas. One customer, in particular, is singled out by the camera; we see her posing like a movie star while she attentively examines the clothes as they flow and flatter the model’s figure. Following the parade, we see four models standing still in front of the camera, filmed in full length, attentive to capture the details of cut, decorations and print fabrics. Later, the designer herself– Palmer–shows the opulent and soft fabric to her clients. The fabric here takes center stage, thus going back to the previous episode of the film that focused on the production of textile and suggesting how its production is the foundation of dress.

There is no doubt that the film is there to advertise Milan as a vibrant and modern city on a par with other important European metropolises. However, more than a promo, the film is remarkable on account of its formal and aesthetic accomplishments. The film juxtaposes factory workers, labourers, passersby in the misty atmosphere of the city early in the morning, tram drivers and market vendors, models in elegant settings, a fashion school, a night club, musicians and dancers. Above all, it juxtaposes people who seem to be stage actors along with people crowding the streets or going about their daily activities and work routines. The second part of the film opens with an episode dedicated to dance; here too we see dress and costume as a key component of the dancers’ gracious movement and rhythm. Some of the shots recall early experiments in filmmaking when a static camera captured movement through the flow of fabric and cloth, as in Louie Fuller’s dance style film. But here, of course, we are at another stage of filmmaking and the camera moves, dances, travels, is positioned on trucks and, in other experiments, on airplanes, to follow the rhythms and speed of modern life. Fashion here adapts to the svelte and dynamic silhouette of an urban woman who is eager to be beautiful and be part of the social scene. The film has, in fact, other shots in dance clubs where young people meet and, towards the end, shots of intermittent lights on a dark screen and in a dark Milan, we see advertising signs (Fiat, Brill, Magnesia etc). Milan appears for sure as a super city, a city of fashion and film, where fashion and film are inextricably bound together.

Military-style overcoat, by Binello Sisters fashion house. Biblioteca Nazionale, Rome.

[i] See Paulicelli E (2004) Fashion under Fascism. Beyond the Black Shirt, Oxford: Berg, for a more extensive treatment of the role of the ENM.

[iii] Emily Braun (2002), “The visual arts: modernism and fascism,” in Lyttleton.

[iv] Luigi Chiarini (1936), “Come si impara a fare il cinema,” in Cinema,reprinted in Orio Caldiron ed. (2002), “Cinema” 1936-1943. Prima del Neorealismo, Rome: Fondazione Scuola Nazinale del Cinema, pp. 70-71.

[v] P.L. Erbaggio (2013), “Nazionale Luce: A National Company with an International Reach,” in Bertellini, Italian Silent Cinema, pp. 221-231.

[vi] Wissinger, E., (2015), This Year’s Model. Fashion, Media, and the Making of Glamour, New York: New York University Press, p. 69.

[vii] Ada Salvatore(1939), “La moda ieri e oggi,” Enciclopedia pratica della casa, Vol. 1, Milan: Garzanti, pp. 531-532.

[viii] Elisa Albano, “Una casa di mode. Palmer” (1919), La Fiaccola. Rassegna Femminile d’Italianità, n 10-11-12, October, November, December. Milan and Rome: Editori Alfieri & Lacroix. I would like to thank Michela De Giorgio for sending me a copy of the article.

[ix] Marta Palmer (1929), “Esiste oggi una vera moda delle vesti?”, L’industria della moda 11:1 (January, 24:27); and “I nostri modelli al Teatro della Moda di Milano”. L’Industria della moda, 11:5 (June): 20-21.