1970s embroidered evening gowns. Annamode. Courtesy Fondazione Annamode

Although Italian style was disseminated and marketed to the world in the years following WWII and in the period of the country’s post-war reconstruction, the cultural and creative traditions on which the success of the Made in Italy and Italian style are based have much deeper roots. This explains why the present study takes as its starting point the modern period, the diva films of the 1910s and the impact they had on the creation of an Italian style and identity. Of course, national identity had been an Italian concern long before cinema came around. In fact, film scholar Giorgio Bertellini (Bertellini, 2000, 2013, 2014) has drawn attention to the fact that the “voyage to Italy” and the many representations of Italy on film were the natural development of the older tradition of the Grand Tour and the picturesque representation of the nation that was transmitted by paintings, photographs and postcards. Several foreign cinematographers and operators, like those sent by the Lumière brothers, filmed Italy, Italian cities and landscapes. But Italy was not only the subject of films, it also had its own industry, an Italian silent cinema that had a golden age lasting from 1908 to 1914 and was successfully exported abroad: “Until 1915, Italian films circulated widely abroad and were extremely popular in Europe, the Americas, and Asia, where they intersected with a variety of societies, cultures, and commercial practices” (Bertellini, 2013, 4).

One of these films was the epic Cabiria, directed in 1914 by Giovanni Patrone. Cabiria became the quintessential emblem of the Romanitas on which Italian nationalism was largely based in the run-up to WWI, and Italy’s entry into it, and later, in the mode of continuity, with the fascist regime. Because of its spectacular cinematography, its nationalist theme, the incredible work of cinematographer Segundo de Chomon, its set design and costumes, Cabiria had a profound impact on D.W. Griffith and was the model for his own 1916 epic, Intolerance. The first fifteen years of the twentieth century were a crucial time in experimental art, technology and cinema; but they were also crucial for the debate that linked fashion and national identity, and where the story of Italian Style has its origins. It was in this period that Italy and Italians became part and object of a cultural production and reproduction that found in film and print culture powerful platforms to portray national identity.

Italian Style focuses on specific films, their forms, styles, and cultural contexts; and on their status as important case studies where fashion intersects with nation. These films maintain what film scholar Dudley Andrews has called their “authoritative status” as vectors of an ongoing discourse on fashion, film and nation, not simply as exemplary illustrations of theories. No book can claim to be exhaustive faced with such a rich and complex topic, especially if that topic is Italy, a country that has so many layers of history and tradition, but also a strong composite identity that is greatly manifested in its cinematography and in its culture of fashion. This study devotes particular attention to films that look and have looked at their historical present in terms of clothing and fashion. This is why costume dramas such as Luchino Visconti’s Il Gattopardo or historical films such as Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Medea or The Gospel according to Matthew are not included. However, a number of illustrations from and references to historical films, from the Tirelli Costumi Company are included.

The study offers an initial map of fashion and film Italian Style where moments of continuity, as well as moments of rupture and experimentation, are charted. A book on Italian fashion and film cannot be solely about directors and actors; it must also be about the costume designers whom directors work with and the costume archives and sartorie on which they draw. Without them, Italian cinema would not be what it is today. Indeed, costume designers and archives are responsible for the synergetic relationship that exists, and has always existed, between Italian fashion and film. As some of the chapters will document, Tirelli Costumi and Annamode are landmark archives that contain not only costumes for the theatre and cinema, but also preserve the work of Italian and international couturiers and give scholars and designers the opportunity to visualize and study their costumes. Costume design for film in Italy is an art that cannot be considered in isolation or apart from the realm of fashion and stardom. Tirelli Costumi and AnnaMode continue today to provide costumes and inspiration for film directors from all over the world and can be considered in their own right as a multidimensional creative laboratory of the Made in Italy.

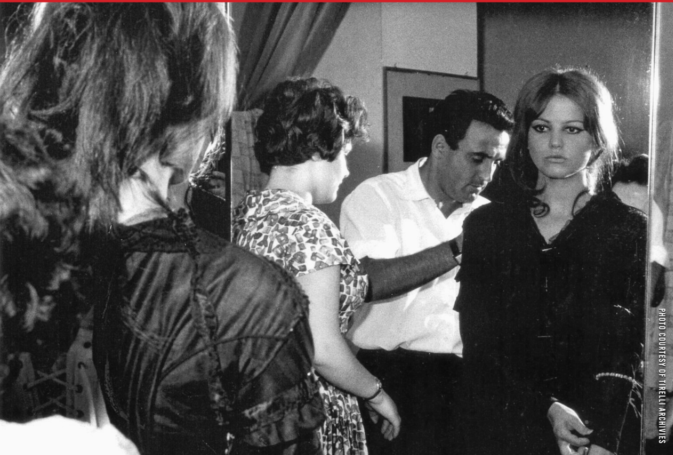

Antonia, Umberto Tirelli and Claudia Cardinale at fitting for film Il Gattopardo, dir. L. Visconti, costumes by Piero Tosi. Courtesy of Fondazione Tirelli- Trappetti

Costume designers such as Piero Tosi, officially recognized with a Hollywood Academy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2013, is but one of the central figures who have contributed to the success of Italian style in cinema through his collaboration with filmmakers such as Luchino Visconti, Pier Paolo Pasolini and others. Tosi, a meticulous philologist, who has obsessively reconstructed the periods, the ambiances, and the feelings of the time through the costumes of the films on which he has worked, has observed that in today’s world the historical costume cannot be reproduced in the way he reproduced it earlier in his career. This change is partly due to the proliferation, multiplication and dissemination of today’s visual sources, whereas before the digital revolution painting seemed to be the privileged source. Nevertheless, costume design cannot be seen as completely separate from the fashion of the time in which the costume is produced. In other words, the revisitation of the past occurs in the context of a present that gazes back on the past. In the 2014 exhibition entitled “I vestiti dei sogni” (The clothing of our dreams), held at Palazzo Braschi in the spectacular Piazza Navona, Rome, after visiting the show and looking at the dress he had designed for Claudia Cardinale in Visconti’s The Leopard, Tosi affirmed that today he would have worked in a completely different manner. Dino Trappetti, who inherited the Tirelli Costumi Company and archive, has also reinforced the idea that costume design today looks at the past and the present in a different manner. He even states in the interview included in the book’s appendix that he would like to produce a small line of clothing with costume designers Tosi and Gabriella Pescucci. One cannot avoid, he says, looking at current fashion, the quintessential manifestation of presentness and nowness, in order to interpret and design an object of the past. This process is triggered today more than ever thanks to the internet and the wide public exposure fashion and couture enjoy. There are of course also economic factors involved in the production of costumes for films. It is not always possible to make new costumes and in many cases costumes can be readapted, recycled and altered in order to fit the needs of a new film. The present triggers and informs the interpretation of the past, even in costume. But temporality and intermediality in fashion and film can also work the other way around, another example of both circularity and negotiation. Period fashion and costume influence the runway and even mass fashion, as did films like Sophia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette (2006), or Baz Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby (2013). In Luhrmann’s film, costume designer Catherine Martin worked with Miuccia Prada and Brooks Brothers to create the twenties inspired costumes worn by the cast. In addition, in his study of Visconti’s Senso (1954), Blom mentions the magnificent costumes realized by Tosi and pinpoints the striking similarities of the silhouettes and details of Livia’s character (played by Alida Valli) and the designs for the evening couture dresses by Balenciaga made popular at the time of the film (Blom, 2006), again a case of intermediality in fashion, costume and film. In other words, costume design needs to be contextualized in the process of filmmaking, and in the larger context of fashion design, art, photography etc.

The costume designer did not appear in an official role in Italian cinema until the 1930s. Before then, actors brought their own clothing to the set. Indeed, their wardrobes were one of their assets and on some occasions was their passport to getting the role. The work of the costume designer in Italy came to be recognized a little bit later than it did in Hollywood. Nevertheless, what both Italy and Hollywood shared was the gradual construction of a “national fashion” through the international dissemination and reputation of cinema. American fashion and an attractive way of life were launched to the masses in Europe through film, especially in the aftermath of WWI. American fashion set out to develop a distinct style and pushed the idea of being independent from Paris, the city that had dominated the world of chic and beauty. Thus, parallels can be drawn between fashion and national identity, and how in both the Italian and US cases it was the power of the media and cinema that made the messages they broadcast particularly persuasive and enabled them to reach large audiences.

In connecting the culture of film and the culture of fashion, I draw on and closely examine a select group of films as case studies. Starting with an examination of early Italian cinema, concentrating on the diva films of Nino Oxilia, Francesca Bertini, Augusto Serena, and Mario Caserini, the study goes on to later periods of great historical and social transformation, from fascism, including directors such as Corrado D’Errico, Alessandro Blasetti, and Mario Camerini, on to the post-war experimentation of Michelangelo Antonioni and the phenomenon known as “Hollywood on the Tiber,” when Italian cinema launched Italian fashion globally with films like Federico Fellini’s La dolce vita, up until today with Paolo Sorrentino’s La Grande Bellezza (The Great Beauty, 2013). As well as considering each film on its own merits, I also aim, first, to indicate how an Italian style was constructed through the intersection of fashion and film; and second, how that intersection was both illustration of and spur to twentieth century Italy’s developing experience of modernity. The study pays a great deal of attention to the period of Italy’s post–war economic boom, a time during which Italian Style and the Made in Italy established themselves as labels and brands that travelled the world. Film and other media facilitated the process of the creation of the Made in Italy, rendering it recognizable and a desirable aesthetic and lifestyle all over the world, a legacy that is still very much alive today. Yet, I also wish to underline that Italy’s fashion-film-modernity nexus had its origins much earlier in the 20th century. That is why the study also gives prominence to the diva films of the 1910s and films made under fascism such as the documentary Stramilano, directed by Corrado D’Errico in 1929, an example of how fashion was part of the identity of a modern city, Milan in this case. The film includes a long fashion show sequence, one of the business entertainments that were heavily promoted by the regime as part of the process of nationalizing Italian fashion, as many of the Luce newsreels testify. However, it was only some years later, in 1937, with Blasetti’s film Contessa di Parma, a film that represents the Italian desire to free itself from the hegemony of Parisian fashion, that we find the first example of a tie-in with the brand name of the Turin based fashion house “Mattè,” the supplier of the film’s costumes. The film itself is set in a fashion house and features the first fashion show in an Italian feature film (such shows had already appeared in several Hollywood films and contributed to the promotion of American fashion and glamour through cinema).

In the 1930s, Gino Carlo Sensani was the first set and costume designer for cinema and, starting in 1935, he held the first chair of Costume Design at the Centro sperimentale di cinematografia (the State School of Cinematography) in Rome, a position he would occupy until his death in 1947. Sensani shaped the education of several costume designers for cinema including Piero Gherardi, but especially Maria De Matteis, who worked on Luchino Visconti’s debut film Ossessione (1942). Matteis’ assistant was Piero Tosi who, as mentioned earlier, went on to work on most of Visconti’s films.

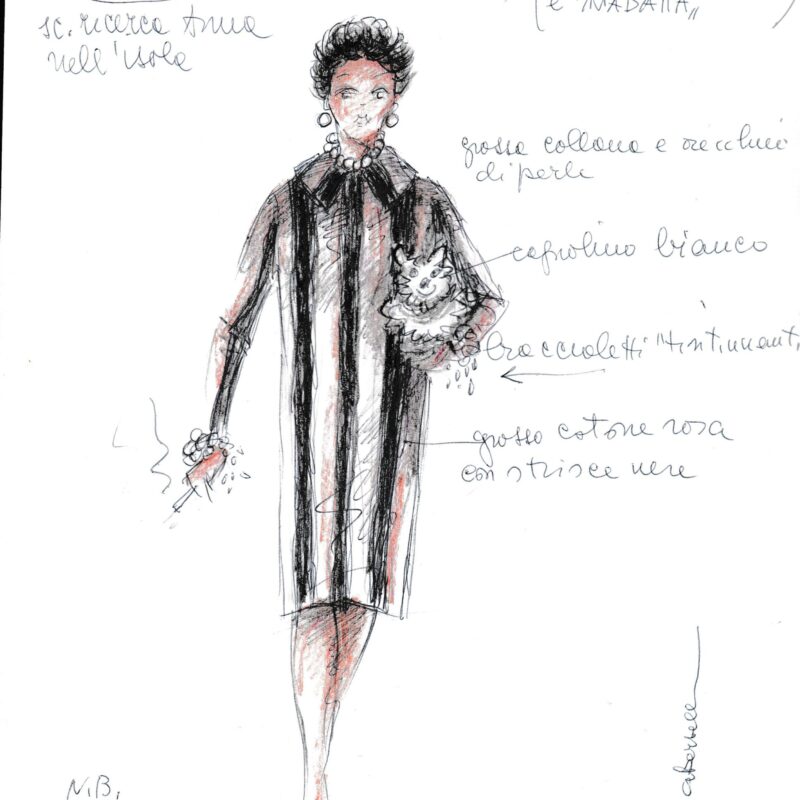

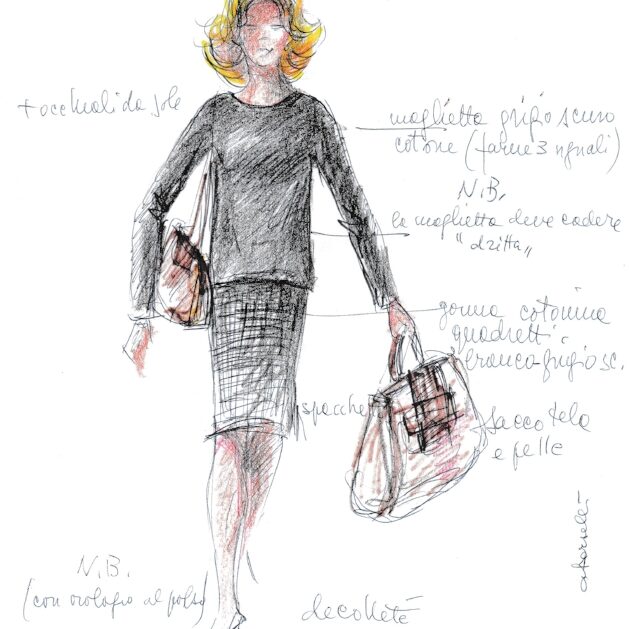

The twin crafts of cinema and fashion and their processes of labour are inherent components of filmmaking and demand to be preserved, understood and valued when we think of the Made in Italy. In the Appendix, the interviews and other texts focus on the role of the sartorie and the clothing archives that are still active today in Rome such as Annamode (interview with one of the two co-founders, Teresa Allegri), Tirelli Costumi (interview with Dino Trappetti) and the Neapolitan atelier of Cesare Attolini (interview with Massimiliano Attolini). Included too are details of the role of costume designers in film and theatre such as Adriana Berselli (who worked on L’Avventura by Michelangelo Antonioni, analysis of whose films takes up a significant part of the book) and an interview with Fernanda Gattinoni. This section of the book aims at giving readers some examples of the craft that lies behind Italian cinema (but, of course, many more could be added), and to encourage reflection on how even auteuresque cinema is always the result of the collective work of specialized and highly skilled artists and artisans. The examples also offer a chance to reflect on the impact of skilled craftsmanship for which Italy is known to the world. In addition, these film and theatre archives are an impressive archive of memory that testifies to the richness of the Italian history of fashion. I also include a translation of the unpublished personal notes Adriana Berselli took when she was a crewmember working on Antonioni’s L’Avventura, filmed at Lisca Bianca in Sicily. The handwritten pages with some drawings by Berselli are also reproduced as images along with the English translation. The interviews with Teresa Allegri and Dino Trappetti aim at illustrating the wealth and tradition of costume design in Italy and how these two important laboratories and institutions, in themselves museums of costumes, contribute to the making of global film and spectacle and to the preservation of an important Italian craft tradition so cherished by international costume designers and filmmakers.

Adriana Berselli, sketches for dresses worn by Claudia (Monica Vitti) in L’avventura, (1960) dir. Michelangelo Antonioni; Sketch for Claudia, (Monica Vitti) and Patrizia (Emeralda Ruspoli), in L’avventura party scene in Palermo, Courtesy of Adriana Berselli.

The interview with Fernanda Gattinoni is an important testimony to that magical period known as “Hollywood on the Tiber,” the topic of one of the sections of chapter 6. She dressed Ingrid Bergman on screen and in life and made some of the costumes for King Vidor’s colossal War and Peace, starring Audrey Hepburn, Mel Ferrer, Anita Ekberg and others. Some of the pictures from Tirelli Costumi, where Bergman’s dresses are held, and the photographs from the Giuseppe Palmas (1918-1977) Archive, serve as further illustration of the role of fashion and film in Italy’s reconstruction during the post-war years but also document the various forms of hybridization between Italy, the US and other foreign countries. The archive is now managed by Giuseppe’s son Roberto whose photographs have also been a rich source for this study and have helped to visually reconstruct this important historical moment of Italy’s post war history. In Rome during the years of the Hollywood on the Tiber, the dolce vita, the Venice Film Festival, and during the awards of the “Nastri d’argento,” Palmas photographed major stars such Sophia Loren, Gina Lollobrigida, Anna Magnani, Ava Gardner, Humphrey Bogart and Laurel Bacall, Audrey Hepburn and Mel Ferrer, Ingrid Bergman and Roberto Rossellini, Gloria Swanson and Salvatore Ferragamo, the American Ambassador Clare Booth Luce and other actresses and models attending the Venice Film Festival such as Ivy Nicholson, Capucine, Myriam Brun, fashion icon and countess Consuelo Crespi as illustrated in the book. Some of Palmas’ photographs look like some of the “paparazzi” scenes in Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita especially those of the arrival of American stars at the airport such as Ava Gardner who was also The Fontana Sisters testimonial, as we will see in chapter 5. In those pictures, in fact we see Micol Fontana, who would become a very good friend of Ava Gardner, welcoming her at the airport in Rome. Palmas also documented the Roman based sartorie such as that of Emilio Schubert, frequented by many actresses who we see posing in his creations, and Princess Irene Galitizine whose pictures are also part of the book. The impact of craft and personalization is central in the interview with Massimiliano Attolini whose sartoria was founded by his grandfather Vincenzo in Naples in the 1930s. It was thanks to Vincenzo that men’s jackets were revolutionized. Cesare Attolini reached notoriety beyond the cognoscendi with Paolo Sorrentino’s film La Grande bellezza with which the book ends.