The Italian Divas and the “Gowns of Emotions”

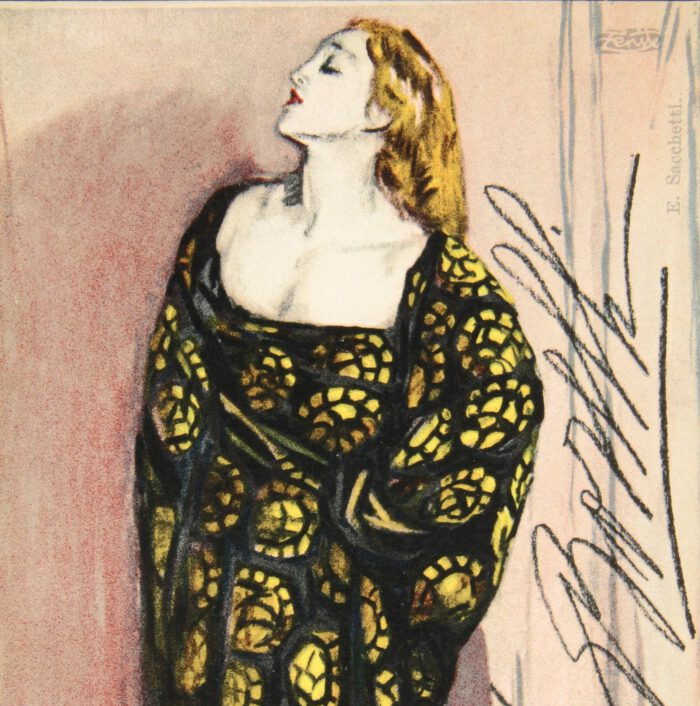

Lyda Borelli, Postcard, Museo Nazionale del Cinema di Torino

The diva films of the early years of the 20th century starring Lyda Borelli and Francesca Bertini “showcased a distinctly Italian style” (Bertellini, 2014, 14). They were the precursors of the Italian and foreign stars who populated Italian cities and Rome in the years of Italy’s post war reconstruction and the parallel phenomenon of divismo. The diva films, and their glamorous actresses are the protagonists of an important debate on identity, style, models of femininity, fashion and modernity that took place in Italy at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Nestoroff? Was it possible? It seemed to be her and yet it seemed not to be. That hair of a strange tawny color, almost coppery, that style of dress, sober, almost stiff, were not hers. But the motion of her slender, exquisite body, with a touch of the feline in the sway of her hips, the head raised high, inclined a little to one side, and that sweet smile on a pair of lips as fresh as a pair of rose leaves, whenever anyone addressed her; those eyes, unnaturally wide, open, greenish, fixed at the same time vacant, and cold in the shadow of their long lashes, were hers, entirely hers, with that certainty all her own that everyone, whatever she might say or ask, would answer yes.

(Luigi Pirandello, Shoot!)[i]

[…] Because everything – from costume and coiffure down to gesture, glance and smile– for each age has a deportment, a glance, a smile of its own. […] This transitory, fugitive element, whose metamorphoses are so rapid, must on no account be despised or dispensed with.

(Charles Baudelaire, “The Painter of Modern Life”)[ii]

In his description of the diva and with his usual wit, Pirandello captures her theatricality and the power of her performance on screen. If, at first, neither physical features nor style of dress identify her, it is the motion of her “slender and exquisite body” that unmistakably tells us who she is. The diva holds the scene, grabbing the imagination of a mesmerized and enslaved audience to such a degree that “everyone, whatever she might say or ask, would answer yes.”

Thus, Nestoroff, the exotic name given by Pirandello to his diva in Shoot!, is the embodiment of a powerful femininity; she is a femme fatale destined for either destruction or self-destruction. The diva does not lose the power and aura she holds in the audience’s imagination even when she dies, either by killing herself on screen or on the stage in front of her lover, as the diva Lyda Borelli does in Mario Caserini’s Ma l’amore mio non muore (1913), the film that launched the genre of the diva film. Once again, Pirandello’s description of the diva captures the essence of her power: motion and gestural performance. The image of the diva is not a static picture. Rather, it is a body in motion.

Lyda Borelli, L’amore mio non muore, 1913, dir. Mario Camerini

Cinema as a powerful vehicle of emotions that affect the imagination and world view of the viewing public (women spectators in particular), who then go on to imitate and reproduce the dresses they have seen worn by the actresses on screen. The movie screen becomes, then, akin to the shop window where women’s desires for fashionable clothing and accessories take on concrete form.

It should be pointed out, though, that the consumer gaze of women spectators “was not merely acquisitive.”[iii] Rather, a more attentive eye towards the complex nuances of the process of negotiating identity and subjectivity for women at this time is needed if we are to have a fuller picture of the role played by fashion and cinema in these early years of the twentieth century. The case of the divas, in fact, helps us understand the dynamics of producing and consuming images and points to how these actresses need to be seen not only in their glamorous on screen dimension, but also as “ladies of Labor and girls of adventure,” to quote an important study by historian Nan Enstad that focuses on American culture at the turn of the twentieth century. Enstad argues that the gaze of women, especially those working class women who became “movie-struck” “was interwoven with complex narratives and fantasies.” She adds that: “When working women gazed at posters, dreamed of stars, and attended shows, they enacted subjectivities in a new public arena and engaged contradictions that they experienced…” in their daily lives.[iv] In the context of Italian culture, the divas were quite a unique phenomenon that was testament to the complexities and contradictions of the process of modernity. Divas brought with them a notion of changing female subjectivities at a time when women in the off-screen world were fighting for the vote and more humane working conditions.

Lyda Borelli, L’amore mio non muore, 1913, dir. Mario Camerini

“La donna e la cinematografia,” an article published in the magazine La Donna in 1916, begins by describing the excitement of the young women working in a milliner’s shop when one of the divas they have seen at the movies, but now in the flesh, is trying on several hats in the midst of a shopping spree:

The bellissima, breezing through the store, was trying on hundreds of little hats, one after the other. […] This no, this yes… One after the other, asthe parade progressed, the purchases were being piled up on a table. The milliner was happy, the customers were amazed. The young women working in the atelier, who were peeping from behind all the doors and curtains – their eyes wide open and having a great time. […]

The frail diva, in her fast automobile coupé, was already going somewhere else to do more shopping. Outside the atelier’s door facing the street, curious and envious eyes of young women were following her, their eyes shining with thousands and thousands of envious desires; one of the apprentices ran towards her car and when she reached it, she threw a small bouquet of flowers to the diva: an homage that was much more eloquent and sincere than those of the aristocratic admirers. [v]

The article gives us both a depiction and a reflection of the impact of cinema on the working class women who admired the diva and fantasized about her. The fantasy induced by the glamour world lived by the actress is accompanied by the apprehension that the new role of women working in the nascent film industry has given them the chance to be paid astronomical salaries. The article mentions, in fact, that Bertini (the diva who came from modest social origins and who could conceivably have been one of the women working in the millinery workshops, atelier and sartorie)had received a salary of 2,500 lire that was then increased during the war to 10,000 lire.

In the article, the power of cinema over the mass audience seems inevitable and parts of modern times, in the same way as the telephone, electric lighting, the newspaper were. Cinema is aligned with the power of the diva to make the magic of the spectacle seductive enough to be dreamed of and imitated:

In Paris as in St. Petersburg, in Italy as in Latin America, the young beauties aspiring to live of love and art are subject to a cult for the great stars of the cinema; each one of them has a favourite: there are some who adore Borelli (in general, men like her more…), there is those who love Bertini (…) There are also those also who judge Menichelli unique […]. All of them end expressingtheir admiration by way of some tangible sign or other, sometimes perhaps unconsciously and inadvertently–they imitate the suffering poses, the gait—the Marquis Colombi would say–a bit rambling, the insistent but pretty sneer. The gentle sex now bertineggia as some time ago it had borrelleggiato or tomorrowmenichellerà. The easy way the queens of the silent film acquired fame and wealth in such a short time is the preferred topic of their conversation. The young women working in workshops know that some of the divas belong to the same breed as they do, who once went to work every morning, and received a poor salary for long hours of work: they speak about their salary, their small town house, their automobile, their stay at the seaside, and their numberless princely admirers. (35)

The article stresses how the motion and gestural performance of the divas defines not only their on screen identity, but also represents a blue print for women of all classes to pose, walk and fantasize:

You laugh at the sartina who touches up her hair copying the pose of Borelli, or the women intellectuals who before entering a drawing room will stay for a few seconds near the door gazing towards the infinite in that narrow space feigning an interrogative gaze a la Bertini. (Emphasis mine, ibidem}

Performances

The divas’ gestural performance is, then, characterized both by motion (duration in film), but also by pose, which represents an interruption in movement, a still image that stems the flow of the film. Specific accessories such as the shawl in Assunta Spina, the Owl Hat in Il Fuoco, have a structural meaning in the context of film and costume. These objects, in calling attention to themselves, become in Bergsonian’s terms “intervals of duration.” At the same time, as philosopher Federico Luisetti has noted in commenting on the futurist photographer Bragaglia’s Bergsonism, these intervals of duration help us to understand the dynamics between movement and pose in the fashion show and on film.[vi] By extension, clothes and accessories act as catalysts in this process of materialization and dematerialization of the visible. Movement and pose, in fact, are the gestures identified by Caroline Evans in her study of the origin of the fashion show, but they are also terms that describe the way the divas parade their costumes on film. Miming both film and photography, the fashion show is characterized by flow and duration as well as by intervals and interruptions through the pose. In the case of the diva films, the plot or the story of the film in question assumes a function that is secondary and subservient to the form of the film.

Lyda Borelli, L’amore mio non muore, 1913, dir. Mario Camerini

In the absence of Italian newsreels of fashion shows during the 1910s, the diva films with the magnificent costumes exhibited on the bodies of Borelli, Bertini, Menichelli and others not only fill this void, but also by way of the high visibility they enjoyed take some of the first steps toward the creation of an Italian style. In this way, dress and costumes on the bodies of the diva play a role in the context of a larger history of the origin of the fashion show as studied by Evans in reference to France and the US. Looking rather closer at the performance of dress in the Italian diva films, we can see how the fashion parades present in them both resemble, but also differ from, the parades organized in France and the US as a spectacle and a marketing strategy for promoting French and American fashion. In the 1910s, an autonomous Italian fashion and an organized infrastructure did not yet exist. This might be the reason why in Italy fashion shows newsreel of the kind produced by Pathé-Fréres or Gaumont and those advertising Poiret’s fashion or the English entrepreneurial dressmaker Lady Duff Gordon (Lucile), which were part of the French fashion scene, were absent.

Lyda Borelli (1887-1959): The ethereal melancholic beauty

Borelli as Salomè, postcard, Album/Art Resource NY

I am very fascinated […] with clothes, with the question of a woman’s elegance, with that fantastic and, without a doubt, complicated world which is a woman’s wardrobe. I, just like you, believe that a wardrobe is a sort of poetic medium or instrument.

(Lyda Borelli, Letter to a writer)

Movement, time, rhythm of the gestures, are all undoubtedly influenced largely by what is worn.

(Georg Simmel, Fashion, 1906, in Purdy, 295

Lyda Borelli, postcard, 1910-18 (b/w photo), Italian Photographer, (20th century) / Private Collection / Alinari / Bridgeman Images

Borelli was such a visible star that Italy gave itself over to a Salomania craze and with it a growing fascination with the orient and the exotic on a par with other European countries and the US. But it was with cinema that Borelli achieved international popularity and a mass audience. The aura that grew up around her and her beauty led to an early manifestation of what today we call celebrity culture. Borelli was certainly the precursor to what later on Hollywood would project through stars like Joan Crawford, Greta Garbo, Bette Davis and others.

The veil: modernity in motion in Nino Oxilia’s Rapsodia Satanica

And as far as people sayingthat the cinema is a new art? Yes it is, in its form[…]Perhaps it is atransformation of the art of posing which Euripides valued so much, after all, precisely because it is the simplest, the dance of human passions—transformed for our modern mentality–[…] I would call the cinema the art of silence in the sense that it is an art of sculptures, one following the other.

(Nino Oxilia, emphasis added)[viii]

A dress wrongly worn is like an adjective that is not appropriate to the name that it is supposed to modify or the object that it is supposed to define. Its intrinsic value is out of tone and it seems that it cannot regain its useful function. This harmony between exteriority and interiority of the artist is as all the more necessary for the cinematographic interpreter as it is more difficult to create a mood in front of the camera if it does not really happen on the set […] And who does not know that emotions are the absolute condition to render the life of creatures in which we have to transform ourselves?

(Lyda Borelli, “Bellezza ed Eleganza,” L’arte muta, I (1916), n. 6-7

Transparent fabric – which also serves practical and morally religious purposes (e.g. as a veil)–and lace (originally a mere luxury product) have received their most refined configuration and most ingenious application only through the creative spirit of eroticism. […] For he knew that clothing is more naked than nakedness, and that we see more behind a veil than in the unveiled…

(Karl Kraus)

Francesca Bertini (1892-1985): the glamorous embodied

Francesca Bertini, c.1921, Italian photographer (20th century), private collection/Alinari/Bridgeman Images

Since the early years of my adolescence, I gave all of myself, with always growing passion, passing through the thorns of obstacles and going on to the roses of hopes and the glowing joys of victories, to the art of silent film,. My daily dream was to climb ever-higher steps on the golden staircase of beauty. This art of oursis like Greek art, it is in the sun, and it has direct relationships with things and nature, it is not a new art, but the continuation of the old thanks to the developments and the unforeseen possibilities that are continuously multiplied by the perfecting of technical elements.

(Francesca Bertini)[x]

As noted by Cristina Jandelli, the public image that Bertini managed to create through the popularity of her many films was consacrated in the postcards that celebrated her beauty. But she kept the details of her private life a mystery. She had delicate features like Borelli, but unlike her, she had dark hair, which lent to one of her screen personae the quintessential representation of the Mediterranean beauty. She says in her autobiography:

I never went out in the evening. Usually I was in bed at nine. Only during the winter months did I go to the Theatre at the Opera […]. I used to arrive late, when the performance had already started and I left before it ended.[…] My lifewas completely immersed in mystery.

Later she says: “Nobody could ever find me, see me or knew where I was.”The strategy of separating her public image from her personal life had the effect of amplifying her attractiveness and cache as a star. In the journal Film, a column called “Piccola Posta dei curiosi” (1916) offers a glimpse of the status she enjoyed. Men sent several letters in which they declared they were madly in love with her, so much so that they wanted to commit suicide; they wanted to know the kind of food she preferred, if she smoked or not etc. Such curiosity towards celebrities is still very present in our post-digital world where the “piccola posta dei curiosi” has been replaced by tweets sent directly by the stars to inform their followers of their lives, daily activities and food preferences. In 1916, the divas epitomized the beginning of celebrity culture and its world of popular press and film gossip. In the rich landscape of magazine publications that flourished in Italy, the journal Film became one of the vehicles that was used to advertise the nascent Italian phenomenon of divismo by publishing several pictures including portraits and set scenes. The fast growing film industry and its female stars were becoming part of mass and popular culture.

Assunta Spina moves and poses on screen, her shawl draped around her shoulder and arms, moving her hands, neck and face; her eyes looking with a certain defiant air. She expresses both the awareness and the pleasure of being in front of the camera. She is not a passive executor or receiver. Even as an object to be regarded, she is also an active producer of her gaze and of her image on screen. In her article “Sensazioni e ricordi,” which appeared in the film journal In Penombra (as shown in the paragraph opening this section), she makes it clear that she took immense pleasure in becoming one of the protagonists of popular culture and the popular imagination. In particular, she notes how cinema as a new medium gave her as an actress the opportunity to delve into a complex process of identity awareness and negotiation of new forms. Some years later, in 1938, she will declare that:

I understood from the very beginning of my involvement with cinema, how this new art would require a simple and humane acting style: an economy of gestures, of attitudes and expressions. Film […} was completely different from the stage. For the most part, my secret consisted in the intuition that allowed me to adjust interpretations to particular needs of cinema. Stylization: here it is in brief, a good definition of my art.[xi]

Bertini, the diva, is then the author of her own image. She legitimates the figure of the artist as a maker; she sees herself at the same level as the men working in the film industry producing dream worlds. New art and technology allowed women like Bertini and other major and minor divas to be protagonists and creators of their own new models of femininity and subjectivity.

Pina Menichelli (1890-1981):

“The Other Woman and the End of An ERA”

Pina Menichelli, c. 1915-25, Italian photographer(20th century) Private collection/Alinari/Bridgeman

Pina Menichelli speaks to me of the role of stage manager in cinema, and we agree completely, because she believes, like me, that the driving force and the creator of a work is the cinematographer. And yet, I add, with all the actresses in cinema that I have interviewed on other occasions, it has never happened that any of them have spoken about the role of the stage manager. (Interview with Pina Menichelli by Giovanni Innocente, In Penombra…)

Eroticism received its essential meaning only with the invention of clothing. The configuration of eroticism has gone hand in hand with the configuration of clothing and in our unconscious experience eroticism and clothing are no longer at all separable from one another.

(Karl Kraus, in Purdy 241-42)

Fashion is a public act. It is the placard, displayed advertising of how one intends to officially manage the business of public morality. Hence, fashion always contains the most precise formula of the general historical situation. “Appearing naked in full dress” is exactly this. For it is nothing other than the solution, construed by moral hypocrisy, to the fashion problem of women’s clothing: to be dressed completely, that is, up to the neck and down to the tips of the toes, and yet also to stand before male fantasy in erotic nudity.

(Edward Fuchs, in Purdy 325)

Pina Menichelli is most remembered for her power of seduction and femininity in sinister and almost diabolic form. The titles of her films–Il Fuoco (1915, dir. Giovanni Pastrone) and Tigre Reale (1916, dir. Giovanni Pastrone), two of her most well known films, both directed by a big name director, Giovanni Pastrone who had just been internationally acclaimed for his big epic production of Cabiria—immediately give the game away. They suggest destructive and seductive power of her beauty and eroticism. She is the sex symbol of Italian divas, far more than her fellow actresses Borelli and Bertini, and epitomizes what Fuchs has identified as the notion of “appearing naked in full dress.” Pina Menichelli represents the “other woman,” the seductress, the femme fatale on the verge of becoming a vamp, an antagonistic spectre to the apparent bourgeois order. Once again, clothing and costume play a pivotal role in the way her erotic charge is conveyed and constructed. Menichelli acknowledges the role played by the direttore di scena (set designer) in the meticulous construction of her image and of films in general, as she made clear in an interview published in the journal In Penombra, quoted in the epigraph to this section. Film, she says, is the result of a collective effort; the diva is the beneficiary of this effort as well as being part of it.

[i] Pirandello, L. [1915], 2005, Shoot! Ibidem, pp.22-23.

[ii] Baudelaire C., [1863] 2004, “Modernity” in Purdy L D ed. The Rise of fashion. A Reader, Minneaopolis: University of Minnesota Press, p 217.

[iii] Nan Enstad, ((1999) Ladies of Labor. Girls of Adventure, New York: Columbia University Press, p. 163.

[iv] Enstad, N. (1999), ibid. p. 163

[vi] Luisetti F. (2015) ibid. p. 7-8.

[vii] Lyda Borelli, quoted in Dalle Vacche.

[viii] Mario Oxilia, quoted in Dalle Vacche.

[ix] Kraus K, (2004), “The Eroticism of Clothes” from Die Fackel (1906)” in Purdy D. L. ed., The Rise of Fashion. A Reader, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 243-44.

[x] This is an article Francesca Bertini published in the journal (1918) In Penombra, “Sensazioni e ricordi. La prima posa,” June, 22-25, p. 25.

[xi] Quoted in Jandelli, C. (2006), Le dive italiane del cinema muto, Palermo: L’Epos, pp. 47-48