Anita Ekberg in La Dolce Vita, 1960, dir. Federico Fellini.

“Hollywood on the Tiber,” was a phenomenon of the 1950s and 1960s, during Italy’s reconstruction and economic boom that was fuelled by the marriage of fashion and film, especially American films shot in Rome. Together, the fashion and film industries helped to construct an attractive image of Italy, turning a nation that was in ruins at the end of WWII into one of the world’s most desirable tourist destinations. The large amount of critical attention that the phenomenon has received has, on the one hand, given special focus to cinema and to Rome, and on the other has offered a mostly descriptive and partial account of the relationship between the films made at that time and the Roman sartorie. Not enough analytical work has been devoted to the role fashion played in defining a narrative of urban experience and desire. In particular, critical studies have overlooked, first, how fashion took a central role in the process of the hybridization of Italian and American cultures; and second, how fashion developed connections with the film industry and the multi-layered history of Rome.

My aim here is to offer some reflections on how the complex phenomenon “Hollywood on the Tiber” paved the way for several important events that were to have profound resonances on the film, fashion, and tourism industries. It was in the early 1950s that the global launch of “Made in Italy” took place. The success that Italian fashion and design enjoyed projected a new image and perception of the Italian peninsula: Italy had become, almost overnight, a modern and appealing country. Italian fashion became sexy and glamorous, thanks to the media and cinema that materialized these new images in the imagination of those who could afford to visit Italy, but also those, the great majority, who were virtual visitors attracted by Italy’s beautiful products and designs, which they saw on screen and in magazines. Since low-cost and more affordable flights were not available, films, as film scholar Pamela Church Gibson puts it, became “air travel,” transporting audiences not only to places they could not afford to visit, but also serving as a showcase for styles and fashions that they might not otherwise see.[i] The fact that many of the Italian films made during this time were shot on location against the backdrop of breath-taking Italian art and architecture contributed enormously to the way cities and Italy as a whole were experienced. It is these links between fashion, film and the specific city of Rome, and how certain films helped to construct a narrative of a glamorous Italian identity that I propose to investigate.

Fernanda Gattinoni and Ingrid Bergman, Rome.

Through the eye it gives to fashion, to the work of fashion houses, to the highly skilled people working in them, and to the emergence of costume designers and creative laboratories for cinema, the chapter also aims at connecting the glamorous side of Italy’s post-war narrative of success with the labour that fuelled and materialized the mediatic success of Rome, fashion and film. These narratives were constructed and sewn with fashion, film and the locations that allowed viewing publics to have the experience of Italy through its cities. The analysis will also offer a wider understanding of how fashion, film and the city shape discourses of modernity and negotiations of individual and collective identities.

In connecting the important objects of experience, fashion, film and the city of Rome, I take my lead from Francesco Casetti whose work has focused on the “filmic experience”. His reflections on experience and the theoretical framework he develops are useful for a better understanding of how the fashion experience too must have a central role in relation to film and the city and how they share, although in different capacities, what we may call the market of experience. Let us see how Casetti defines the meanings and function of the “filmic experience” and its overlap with the fashion experience. In Casetti’s words:

… a discourse is always a representation, but also an action. On this note, one can say with certainty that the filmic experience is not really a filmic experience if it is not certified at the level of discourse as well; it is this certification that leads to the emergence of that social and individual consciousness without which the filmic experience would not effectively exist. In other words, the filmic experience, like any other experience, would not be such if it did not find an echo in the network of the discourses that surround it.[ii]

Casetti goes on to say that if cinema “thanks to its apparatus, embodies the real […], fashion takes the process of embodiment almost literally.” In fact, if cinema provides the means for a virtual or symbolic identification (“mental garments” as Casetti calls them), fashion “responds quicker and more aptly to the needs of expressing/ performing oneself.” In his most recent book, The Lumière Galaxy (2015),Casetti has further explained that experience is a “Cognitive act, but one that is always rooted in, and affects, a body (it is ‘embodied’), a culture (it is ‘embedded’), and a situation (it is ‘grounded’).”[iii] As these three levels work interchangeably, we can use them to connect fashion, film and the city. Further clarification, however, is needed to explore the meanings and implications of experience in our context as both fashion and film bear on implications with the senses (Casetti’s embodied experience). The typology, however, is and could be different: in wearing clothing, one has an immediate physical, bodily and symbolic response to the object one is wearing. Clothing, though, also elicits a response from people looking at the wearer. A wearable object can also be possessed in one’s wardrobe. But just as clothes can be worn so can the symbolic experience of living a city be worn. We can “wear” the city of Rome without actually being there, but simply by being made aware of the city and all it is made to stand for, just as people the world over wore Rome after seeing the glamourized representations of it on the screens of their local cinemas.

“Wearing” a city is, then, —-in Casetti’s terms–symbolic, both embedded insofar as it is part of a cultural discourse and grounded insofar as Rome was a city that actually existed, even though many of the people who invested in the cultural discourse of the city had never ever set foot there. For generations of viewers, iconic films such as Roman Holiday or La Dolce Vita have spurred a process of desire that has led to a symbolic wearing of the city simply because the spectator acquires the experience of fashion, film and the city. Fashion, style and film are sewn on the body of the city at different levels of the imagination. In this way fashion, film and the city create a sensuous and emotional experience in which there are inter-exchanges of different domains and affective layers. In other words, the experience of cinema is, first, optical, and then becomes haptic thanks to the presence on screen of fashion and clothing; the experience of fashion is, first, haptic, and then becomes optical. The city, Rome in our case, becomes the site in which optical and haptic experiences and discourses take shape and render lived experience palpable, readable and consumable. Fashion functions as both an optical and haptic devise that binds together the different levels of experience. However, each discourse that surrounds the lived experience of fashion and film requires that it be contextualized and historicized.

Ingrid Bergman, in Viaggio in Italia (1954), dir. Roberto Rossellini.

Robert Gordon has discussed the inter-textual relationship between Roman Holiday and La Dolce Vita as two interrelated iconic “snapshots from a proliferating web of connection and hybridisation between 1950s Hollywood and Italy.”[iv] I would add that fashion and the parallel development of costume design for cinema in Rome also contributes greatly to this process of Italian and American hybridization.

It was thanks to the success and widespread diffusion of the “Hollywood on the Tiber” phenomenon that Rome came to be perceived as a “filmic and fashion experience” to be lived and consumed by the city’s visitors, largely on account of its history, art and architecture. Rome itself, then, became an object of experience similar to the ones engendered by film and fashion. Rome came to embody a series of emotional experiences and fantasies that had a special force for visitors from outside or abroad and constructed for them a picture not only of the city but of the whole nation. As Angelo Restivo has noted “Rome remains throughout [the economic boom] the centre of image production within the nation, so that the Roman story stands in for the story of the nation itself.”[v] In the same vein, the major producers of images—fashion and film–mediate and materialize the urban experience, shape personal and collective identities and shape the myths of the city.

Linda Christian in her wedding dress at the Fontana Sisters Atelier, Rome, 1949.

Fashion houses such as the Fontana Sisters (located in Piazza di Spagna) and Fernanda Gattinoni (near Via Veneto and strategically close to the American embassy and Rome’s nightlife) were instrumental in establishing the relationship between glamour, cinema, and the city. They designed and collaborated with American costume designers to make clothes for the stars in the films made in Italy. This was a sign of a further step in the process of the hybridization of the relationship between Italy and US. Fashion shows, fashion parades and models appeared in films, a trend that had begun in the 1930s, as we have seen. But fashion shows within film narratives became much more prominent in the post-war years. Luciano Emmer sets his film Le ragazze di Piazza di Spagna (1951), starring Lucia Bosè, in the Fontana Atelier in Rome in Via Sebastianello.[vi] In the same year, the couturier Schubert, playing himself, helped the aspiring new star Sophia Loren put on a dress in the film Era lui, sì, sì (It was him, yes, yes, 1951), directed by Mario Girolami, Marcello Marchesi and Vittorio Metz. Figure, Schubert Sophia Loren Palmas Other US and world cinema stars– Ingrid Bergman, Ava Gardner, and Cary Grant, as well as Peck and Hepburn– followed and Italian fashion designers capitalized on the presence, fame and glamour of their clients and used them as vehicles to elevate the increasingly international status of Italian fashion.

The Fontana Sisters created a dress called ‘Roma antica’ (Ancient Rome) for Ava Gardner, one of the American ambassadors of Italian fashion, who was invited to Grace Kelly’s wedding in 1956. Ava Gardner was a personal friend of the Fontana sisters, especially Micol, and was their testimonial in several fashion shows. In addition, she was very taken by the elaborate and glamorous evening gowns produced by the Fontana atelier. They can be admired in Mankiewicz’s film The Barefoot Contessa (1954) where Gardner wears colourful and spectacular crafted designs that are exquisitely embroidered and decorated. As Stella Bruzzi has argued, “this close relationship between couture house and individual star has proved an enduring and essential component of the history of fashion’s association with cinema” (165).[vii] The increasingly hegemonic role played by Rome and the city’s designers in dictating what was fashionable also led to changes in men’s fashion. In the early 1950s, along with women’s fashion, men’s fashion—whose sartorial elegance was epitomized by Brioni’s ‘Roman style’—was also presented at the Sala Bianca. Launched as a brand in 1952, Brioni’s ‘Roman style’ was, in the early 1960s, given even greater exposure by the continental suit that had first made its appearance in the late 1950s, worn by Marcello Mastroianni in La Dolce Vita. Italy has had an important role in tailoring men’s fashion the world over, following a well-established sartorial male tradition in Naples, Milan, and especially Rome. The Neapolitan suit was to bring about a sartorial revolution insofar as its cut softened the male jacket, as we can see in the documentary O’Mast, made by Gianluca Migliarotti in 2011. As Glenn Adamson notes, the Neapolitan jacket had radical effects on menswear and offered itself as an alternative to the British hegemony of the traditional Saville Row style. He argues, in fact, that in 1932 when Rubinacci opened his tailor shop in Naples he called it “London House” in order to attract the local sophisticated male clientele. For male fashion, London was the counterpart to Paris at that time. Adamson reports that: “Fast-forward to the year 2000. In that year, Italy exported 28 million pounds worth of suits to the UK and imported less than ₤1 million pounds worth of British suits in return.” This, he says, is “one of the great success stories of twentieth century Italian fashion” (Adamson 218).[viii]

Marcello Mastroianni in La Dolce Vita, 1960, dir. Federico Fellini.

In fact, a different image of masculinity was taking shape at this time, thanks to a suit that was gradually dispensing with its armour-like stiff edges, and now embraced the body with soft fabrics and sartorial fineness of detail. In addition, a colour revolution in men’s wear put an end to what Flügel had defined as the “Great Male Renunciation.” Brioni, for instance, introduced red for men’s evening wear; Angelo Litrico created a purple dinner jacket in 1956 and borrowed from women’s wardrobes for his experimentation with colour for men’s wear.[ix]

Monica Vitti in L’eclisse (1962), dir. Michelangelo Antonioni.

Through fashion and cinema, Rome began to project an image of glamour, art, and beauty and gained the status of a leading fashion city. Later, the crucial 1950s and 1960s—years of the post-war ‘economic miracle’—were defining times for the Italian capital in the larger global economy and the identity of Rome, ever more shaped through American mediation, was made possible by popular culture, fashion, film, photography, and sanctioned the idea of Italy as place for fashion and style.[x] Fashion was in the forefront in telling this complex story of how different systems of cultural mediation (film, journalism, art, architecture, etc.) made critical contributions to our understanding and experience of Rome and Italy, declined in the past, in the present or in terms of an aspiring dream or destination.

For the foreign press, buyers, visitors and movie people, Italy and its cities and especially Rome, became an unforgettable sartorial, cultural, and personal experience of the type so often romanticized in literature and cinema. Wearing Italian, especially Roman, fashion meant wearing Italy’s culture, its breath-taking artistic heritage; or, in other words, it meant wearing and embracing the country and its unique and beautiful cities.

Gallery: Lace evening dress by Fernanda Gattinoni from Ingrid Bergman wardrobe donated to Tirelli Costumi, Rome.

Photo by Fiorenzo Niccoli, Courtesy Tirelli Costumi.

From a more prosaic standpoint, filming in Cinecittà was also much cheaper for American filmmakers as they received a tax break that made the cultural exchange even more attractive; in addition, for their film costumes American film directors relied on the expertise, knowhow and creativity of Italian ateliers and the more specialized theatre/film costume houses such as AnnaMode, Tirelli, Farani, Safas and others related to accessories and wigs like Rocchetti.[xi]

The 1950s and 1960s were a vibrant time to be in Rome. The city was a magnet that attracted both foreign and Italian filmmakers, a locus of a creativity that revitalized design, fashion, and the arts in general. A vital synergy involved filmmakers, journalists, writers, artists, costume designers, fashion atelier and stars that manifested itself in the richness and complexity of the culture during the Hollywood on the Tiber epoch. Rome as a city—and as an idea—became an ongoing ‘dream spectacle,’ a promised land for visitors from abroad and from the Italian provinces who hoped to play a part on the city’s stage.

No other film better than Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, has been able to capture the essence and the complexity of life in Rome in the wake of Hollywood on the Tiber. As film historian Peter Bondanella has noted, with the appearance of La Dolce Vita “the focus of international cinema was as much upon the Eternal City as on Los Angeles” (Bondanella 68).[xii] Via Veneto, as depicted in La Dolce Vita,became the hub of Roman night life where stars and celebrities met and where the work of celebrity journalists such as Marcello Rubini (Marcello Mastroianni)—reporting on high society gossip–became an industry in itself. The photographers who had the task of capturing sensational scoops for gossip columns and tabloids also became celebrities. Walter Paparazzo, the photographer who accompanies Marcello on his journalistic assignments, is the origin of the new word , which has since entered the English language. One of Rome’s most well known shoemakers, Alberto Dal Co’, whose shoes were worn by many celebrities, designed a shoe called Paparazzo in 1960, which must have been inspired by Fellini’s movie. The Paparazzo shoe is a high heel stiletto pump with a pointed shape ending with a metal ornament that seems to be somewhere between an orientalist touch and a tool for self-defence.[xiii] In fact, Dal Co’s shoe seems appropriate as a form of stylish self-defence of the diva as she is being followed by paparazzi. Capturing this tabloid sensationalism, in La Dolce vita, Fellini continued the story that he had begun in the White Sheik. He offers a spectacle of the role of fantasy and desire in the creation of modern myths and in the movie star cult of personality with all its excesses. La Dolce vita is a powerful tactile spectacle of life in Rome during the boom, but it is also a timeless theatre that shows Rome off as spectacle and puts on display the power of costuming and fashion. The marvellous sets and costumes designed by Piero Gherardi in collaboration with Fellini are still to this day the inspiration and materialization of Italian Style. Thanks to Fellini, the name Dolce Vita has become a powerful trope that signifies in Italy, but especially abroad, Italian style, fashion and glamour. In La Dolce Vita, Anita Ekberg epitomizes the Hollywood diva who comes to Rome to star in a film and who refashions herself in Italian garb. In the much cited sequence when she walks at night with Marcello through the Roman side streets with a cat on her head, we see her all of a sudden captivated and mesmerized by the sight of the baroque Fontana di Trevi, her eyes opened to the sublime beauty that is Rome, but it is a beauty that was reproduced by Fellini in the studio (“Fellini”’s Trevi Fountain can still be seen today on a sound stage in Cinecittà).

Roma: Fellini’s Roma (1971)

In La Dolce Vita, the traces of the past are filtered through presentness and the now is couched in the gestural incertitude of Marcello on the beach between the dead sea monster and Paola, the girl with the face of an Umbrian angel; in Roma, though,Fellini takes us on a profound journey of exploration into the seams of the historical past. The present explodes in the intermittent lightness and darkness, pastness and presentness of the dreamlike journey of history. Fascist Italy and WWII recur in each re-visitation of present Roman sites and contexts; in many scenes Fellini shows us flickering lights that alternate with darkness, suggesting the co-presence of opposites and a reality that can only be glimpsed through its traces and intermittent sparks.

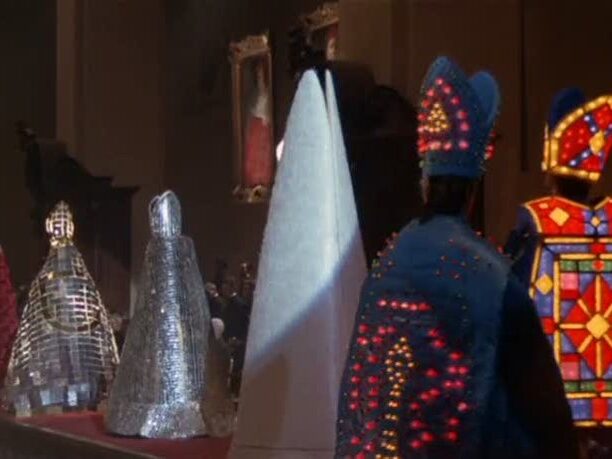

The Ecclesiastical Fashion Show

The ecclesiastical fashion show in Roma is the longest fashion parade on film. It lasts 15 minutes plus. On the circular catwalk, the models are not selling or promoting any particular design as was the case of Blasetti’s Contessa di Parma or D’Errico’s Stramilano. It is pure performance. The ecclesiastical parade in Roma is the culmination of pastiche, bricolage; the most excessive moment in Fellini’s spectacularization of the real held under a magnifying lens. Already in its different episodes, the eternal city has been made to appear as an incredible costume parade where the Fascist and ancient pasts intermingle with the present in a recurring historical citation. The ghosts of the past, and especially those of Fascist Italy, punctuate the story and animate the myths of the present. In Rome, the past appears and reappears in intermittent mode, each time with a different tone and light, sometimes as a parody, other times as the grotesque, or with the almost innocent eye of youth, recovered in first sexual experiences in the brothel etc., and as the Dolce vita revisited after more than a decade.

Fellini dedicated a great deal of attention and work to the ecclesiastical show. Two of his illustrated notebooks, one entitled “Defilé” and the other “Gli aristocratici e il defilé” were dedicated to this sequence. Danilo Donati, the costume designer who worked with Fellini on Roma collaborated with two sartorie in Rome, Farani and Tirelli, on the costumes. The apotheosis of Roma comes with the ecclesiastical fashion show on the catwalk, an episode tellingly situated between the whores’ fashion parade in the Fascist brothel and the festa de noiatri (the feast of us all) held in Trastevere, with its parade of food and drinks. Here, among the people sitting at the tables, the viewer encounters American iconoclast Gore Vidal, who is asked why foreigners–and especially Americans–are attracted to Rome. Vidal answers: “Rome is the city of illusions. The ideal place to see the end.” That sense of death and decay is also present in the fashion show, where parody and the grotesque reach disturbing heights. It is a tour de force in which elements of theatricality, ritual, intricate dress, colour, and texture typically associated with the elaborate rituals of the Catholic Church are revisited in surrealist mode. At the same time, the fashion show conveys a haptic and optical experience of clothing as spectacle. On screen, we see silks, lace, luxury fabrics, light hats and veils; exquisite attention is given to details and workmanship, crystals and beading, sequins that cover the bodies of the unusual ecclesiastical models. Donati is the magician; Fellini the creator of illusions. In actual fact, no luxurious fabrics were used for these costumes. The spectacular garb in which priests, nuns, cardinals and even the Pope appear on the catwalk was actually realized, despite its opulent appearance, with poor material. Donati was a very inventive designer who could translate into costumes the most extreme ideas of the filmmakers, as he did with the incredible costumes we see in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s final film Salò, le 120 giornate di Sodoma (1975). Donati’s costumes for Roma tell the story more eloquently than dialogue. His volumetric approach to texture and space is crucial for the catwalk in Fellini’s film.[xiv] Instead of shiny fabrics, the costume designer used iridescent gift-wrapping paper and many lights and colourful decorations to embellish the mitre of the prelates as if they were Christmas decorations; small bulbs from an amusement Park; the “lace” actually comes from big cake paper.

The ecclesiastical catwalk, Roma, dir. Federico Fellini, ULTRA FILMS/PRODS ARTISTES ASSOCIES / THE KOBAL COLLECTION, Art Resource/NY

Among the “aahs” of the audience, the Pope himself appears on the catwalk towards the end of the show (in the place where a bride would appear in a conventional fashion show). The human shapes of the models turn into machines, robotic bodies with clothes that walk by themselves, without a body inside them. In his notes on the defilé to Danilo Donati, Fellini writes: “remember a cardinal like a flipper […] an (invisible?) cardinal alone electric-like” (Lo Vetro, 2015, 24)

Costumes become independent forms; dressing up calls attention to the very process of illusion, distortion, and representation, all integral Fellinian parts of reality and its construction. The ecclesiastical fashion show, set in Rome and performed by Roman representatives of both Church and aristocracy, ultimately erodes the separation between audience and spectacle, corroding the borders of image and identity, self and otherness.

In Roma, Fellini announces the end of an era and the self parody of institutions, spaces of leisure and consumption, and icons representing the city’s ‘identity’: the pope appearing in a fashion show, Anna Magnani playing herself, going home and closing the door on Fellini’s camera, the semi-orgiastic feasts of food and people out in the street, and of course Fellini himself who is a constant presence in the film, in person and with his off-screen voice.

Fellini’s Roma and the crucial role that costume and fashion play within its narrative is part of the film’s blurring of the boundaries between the lived, real Rome, on the one hand, and the imagined, fantasized Rome on the other. Both cities, however, carry equal weight. With their magnifying lenses, fashion and cinema disfigure representation of cities and places and reveal their most profound and hidden truths.

Rome & Fendi

Rome, the eternal city of fashion and film continues to hold a special role in the ongoing process of branding and re-branding as discussed in Italian Style.

The re-branding process of FENDI, a couture maison, has long been identified with the city of Rome.

Fendi, now owned by LVMH, which enjoyed the important creative and design input of Karl Lagerfeld, has recently celebrated its 90th anniversary with a spectacular and unusual, although very cinematic, fashion show. Models paraded along Plexiglas catwalks placed over the Trevi Fountain, the landmark site of one of the most memorable scenes of Fellini’s La Dolce Vita.

As French critic André Bazin had noted in talking about Italian post-war cinema, the landmark buildings, architecture and archeological sites of Italian cities are the ideal sets for filming on location. Italian cities are tangible and consumable sites for film, fashion and fantasy, the name chosen by Fendi–“Legends and Fairytales” –for their collection of furs.

As French critic André Bazin had noted in talking about Italian post-war cinema, the landmark buildings, architecture and archeological sites of Italian cities are the ideal sets for filming on location. Italian cities are tangible and consumable sites for film, fashion and fantasy, the name chosen by Fendi–“Legends and Fairytales” –for their collection of furs.

Fendi has also supported the restoration of the Trevi Fountain. The fashion show also sealed this double celebration. At the end of the show Karl Lagerfeld walked onto the catwalk with Silvia Venturini Fendi, greeting the audience and throwing, as traditions wants, a coin into the fountain.

On October 23rd 2015, Fendi inaugurated its new headquarters in another incredible landmark building, the Palazzo della Civiltà italiana (also known as Il Colosseo Quadrato). The building was commissioned and work on it began in 1938. Mussolini wanted it ready for the World Expo that was supposed to take place in Rome in 1942, but because of WWII the exhibition never took place and the Palazzo della civiltà was completed only in the post-war period.

Victory Boyko Via Getty Images

To celebrate its new headquarters, in October Fendi hosted an exhibition entitled “Una nuova Roma. L’EUR e il palazzo della civiltà italiana” (A new Rome. The EUR and the Palace of Italian Civilization). Clips from films by Antonioni, Fellini, Pietrangeli, Bertolucci and others in which the Colosseo quadrato appeared were shown.

[i] Church-Gibson, 2006, p.93.

[ii] Casetti, pp. 7-8.

[iii] Casetti, 2015, p.5.

[iv] Gordon, 2014, p.129.

[v] Restivo, 2002, 46.

[vi] See Eugenia Paulicelli, “Cronaca di un amore: Fashion and Italian Cinema in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Films (1949-1955)”, in ed. Graziella Parati, New Perspectives in Italian Cultural Studies (Madison: Farleigh Dickinson University Press, 2013), pp. 107-131.

[vii] Bruzzi S. (2013), “Italian Fashion Designers in Hollywood” in Stanfill S. ed. The Glamour of Italian Fashion, London: V & A Publication.

[viii] Adamson G. (2013) “The Neapolitan Jacket makes a vivid contrast with a traditional Saville Row jacket” in Stanfill S. The Glamour of Italian Fashion, London: V & A Publication.

[ix]In 2010, an exhibition Fashion + Film. The 1960s Revisited was held at the James Gallery at the CUNY Graduate Center. On view was a red velvet morning jacket (1952) by Brioni.

[x] Guido Crainz, Storia del miracolo italiano. Culture, identità, trasformazioni fra anni cinquanta e sessanta (Donzelli: Rome, 2005).

[xi] See the documentary by Guido Torlonia, Handmade Cinema (2012).

[xii] Bondanella P. (2002), The Films of Federico Fellini, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[xiii] Ferraro P., (2013), La moda italiana nel cinema dal ventennio fascista alla dolce vita, Padua: Esedra Editrice,; see also Koda H. (2011) ed. 100 Shoes, intro. By Sarah Jessica Parker, New York: The Costume Institute at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

[xiv] In 2014 an exhibition on Danilo Donati and the Farani sartoria has been organized at the Villa Manin in Passariano, Udine. The catalogue from the show is titled, Trame di Cinema. Danilo Donati e la sartorial Farani, Milan: Silvana.